John Creighton Campbell co-authored “The Art of Balance in Health Policy: Maintaining Japan’s Low-Cost, Egalitarian System.”

John Creighton Campbell co-authored “The Art of Balance in Health Policy: Maintaining Japan’s Low-Cost, Egalitarian System.”

Dr. Campbell spoke with the freelance writer Sarah Arnquist:

How does the Japanese system provide health care at lower cost than the American system?

- Life expectancy: 83 years

- Infant mortality: 3 per 1,000 live births

- Health spending as a percentage of GDP: 8

- Percentage of health spending that is private: 18

- Doctors per 10,000 people: 21

Source: World Health Organization. U.S. statistics.

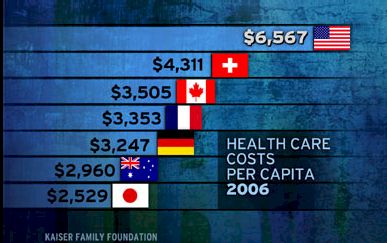

Japan has about the lowest per capita health care costs among the advanced nations of the world, and its population is the healthiest. That is largely due to lifestyle factors, such as low rates of obesity and violence, but the widespread availability of high-quality health care is also important. Everyone in Japan is covered by insurance for medical and dental care and drugs. People pay premiums proportional to their income to join the insurance pool determined by their place of work or residence. Insurers do not compete, and they all cover the same services and drugs for the same price, so the paperwork is minimal. Patients freely choose their providers, and doctors freely choose the procedures, tests and medications for their patients.

Reimbursement rates to doctors and hospitals are negotiated and set every two years. The fees are quite low, often one-third to one-half of prices in the United States. Relatively speaking, primary care is more profitable than highly specialized care, so Japanese doctors face different incentives than U.S. doctors. As a result, the Japanese are three times more likely than Americans to go to the doctor, but they receive many fewer surgical operations.

What does the Japanese health system do particularly well?

First, Japan is egalitarian and medical bankruptcy is unknown. An individual’s income influences the quantity and quality of medical care probably less than in any other country. Premiums and out-of-pocket costs are minor concerns for most, and low-income people and the elderly receive subsidies to afford care.

Second, the Japanese system is quite good for chronic care, particularly because it has so many older people. Along with appropriate medical care, Japan also provides long-term care to all older people who need it through a public insurance system that started in 2000.

What is your biggest criticism of it?

Financial stringency and organizational rigidities have led to inadequate hospital services in some areas, particularly in emergency care, where patients in ambulances are sometimes turned away. There also are doctor shortages in some regions and specialties. Consultation times can be too short for complicated diagnoses and for psychotherapy. Specialized training and certification for physicians should be better, and cutting-edge surgical techniques should be more available.

Many of the problems are largely due to underinvestment, and the severity of the cost control has become an issue in the current election campaign.

What is the most important lesson Americans should learn from the Japanese system?

In the 1980s, health care spending was increasing as quickly in Japan as in America, but the Japanese government learned how to influence medical care provision without rationing by manipulating how it paid for services. Annual spending growth has thus been quite low despite a rapidly aging population. Including everyone in a controllable system was a prerequisite. Japan is not a single-payer system, but like France and Germany, it has been able to control costs by tightly regulating multiple insurers.

Source: New York Times Article by By Sarah Arnquist at http://prescriptions.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/25/health-care-abroad-japan/?hp